A fiction revolving around the life and times of India’s estimated 40 lakh delivery workers is forcing many to think about tensions revolving around this godforsaken profession.

And more importantly, whether this profession should definitely work within time limits and better emoluments.

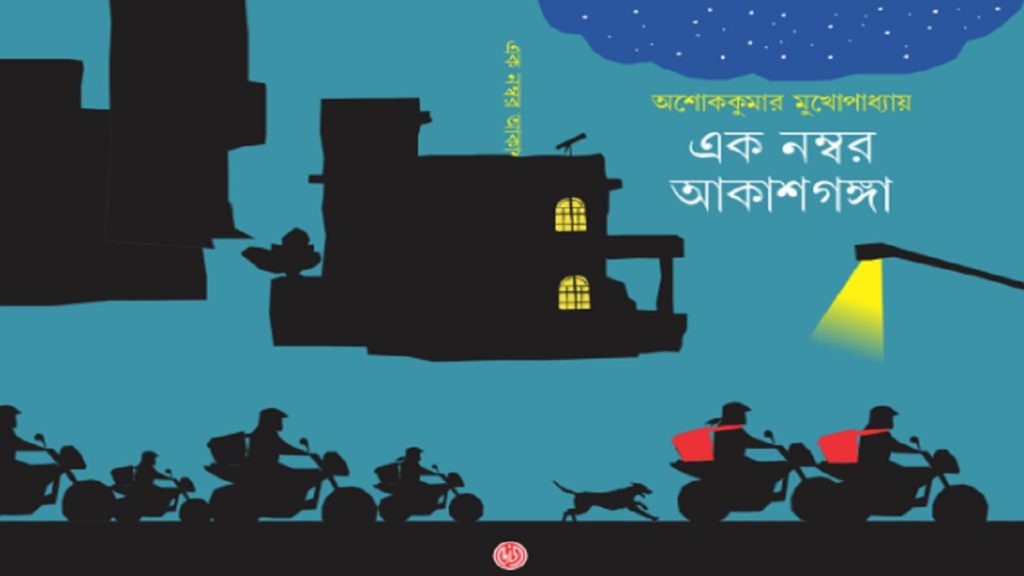

But hold it, the book is making waves among Bengalis in Bengal and among Bengalis in some parts of the country. The tome, Ek Nombor Akashganga that translates into Number 1, AkashGanga (a house in North Kolkata that is home to the gig workers) is brilliantly written in Bengali. The author, Ashok Mukhopadhyay, has not translated it into English. But there are high chances that this book will be translated, like numerous books in India which are first printed in regional languages and then translated in English.

The protagonist of the novel is one faceless Sriman Kundu who works for long hours for deliveries – even in torrential rains or foggy Kolkata – and routinely faces insults from clients ordering food. And there are times when Mondal gets into trouble and runs for his life. Else he knows he will be hit.

Kundu knows he could easily be 23 year-old Mohammad Rizwan, a delivery boy who on 20th January, 2023, was critically injured while delivering a food order to an upper-middle class neighborhood in Hyderabad, the capital of India’s southern state of Telangana. Rizwan had arrived at the delivery location around 2200 hours, and the entrance was wide open. A dog lunged at him, causing him to fall from the third-floor balcony. The customer left Rizwan at a hospital, without paying for his treatment. Rizwan died three days later.

Mondal is alive, he is lucky. Twice he was faced with humiliating situations that almost drove him to death. The author explains why local, online food-delivery platforms rarely care about gig workers and normally hire them on contract or as temporary workers. The International Labour Organisation (ILP) says this is a common practice among platform workers in developing countries so they can get enough gigs and earn sufficient income.

The book explains why these gig workers do not have any respite from their gruelling hours of duty, often their bosses ask them to find a new planet where work hours would be less. That is an insult and also an indication that an immediate sack could happen.

It is a tough, tough life, says the author. The gig workers are working-class people and if they do not earn, they cannot pay rent or put food on plates. So the alternative is to drive, drive and drive. And drive in all conditions, all the time. And they must have a smartphone and a motorbike.

When an accident happens, no one stands by. Worse, communications representatives of online portals paint a different narrative to save their client’s skin. On many occasions, companies say the gig worker in trouble was not even registered as a delivery partner. There goes your chances for compensation, says the book. But no one asks the company why it should not verify people working for them. And if they do not pay attention, is it not their fault?

It is, but who will bell the cats?

The book reminds us India’s gig workforce is expected to expand to nearly 24 million by 2029. Currently, gig work contributes over one billion dollars annually to the Indian economy. Platform workers comprise a significant portion of the gig workforce.

Let us return to the book. Kundu has been rammed by a big car and he is all blood on the pavement. But Kundu gathers courage and walks upto a clinic. A para-medic bandages him up and Kundu is back on his bike because four more orders have come. His superior is aware of the accident but cares little about Kundu. “Let me find you a better planet where you will have to work less,” the boss has sarcasm laced all over his words.

Throughout 2022, the Indian media reported several incidents of road accidents, assaults, and discrimination over religious and caste identities of hapless delivery boys and other platform workers. The media further said these incidents often led to their deaths or caused physical injuries, mental agony and loss of earnings.

Consider the case where Kundu is told by his colleague that he has lost his motorbike, someone stole it. So what is the answer? He must get a bike from someone – beg, borrow or steal – and continue the rides. Isn’t it inhuman? It is, but that is the harsh reality of these gig riders.

These gig riders are referred to as “partners” or “independent contractors” by their companies, they remain outside the traditional employer-employee relationship. They are rarely provided with protection against the risks they regularly face. Experts say in a sector where workers are not collectivized, making claims becomes difficult.

So what happens? The gig workers often find the process challenging due to a lack of literacy and the paperwork. It is never in place. Worse, in many cases, platforms companies erase the workers’ work history so they are unable to make any claims.

But solace comes for Kundu when people in almost similar businesses react, smash the face of someone with nonsensical behaviour. Like this female two-wheeler driver did, smashing a drunkard out of shape with a karate chop. That’s not the best of the ways to handle a crisis but it definitely sends the right, the perfect signals.

Some stay and survive, some drop out and pick up odd-jobs at the warehouses of medical companies for low cash. The book brilliantly brings out the pains, the agonies, the frustrations of the gig workers.

Shouldn’t the government intervene? It should. People at the top should understand that the Indian society is now seriously shifting towards gig work and it is for the government to address the inequality between salaried and gig workers. New laws guaranteeing social security and occupational health and safety workers were passed more than three years ago by Parliament.

They have not been implemented. Why? No one has an answer. In the long run, this will only worsen unemployment and burden the health-care system.

No one is listening, no one cares.

Time for Kundu to start his motorbike. Someone is screaming into his handset: “God damn it boy, when will you deliver the packet?”

A brilliant read.